The Stó:lō “People of the River”

The Stó:lō people, Mission’s first inhabitants, have lived in the area for at least 4,000 to 10,000 years, and are the architects of Mission’s Xa:ytem Rock, one of Canada’s oldest archaeological findings. Their traditional territory extends across the Fraser Valley and the Fraser Canyon. As part of a larger First Nations group, the Coast Salish Peoples of the Pacific Northwest, much of their traditional lifestyle is based around the subsistence gathering of local plants, hunting, fishing, and trading goods with other Coast Salish Peoples. Speaking Halq’eméylem (a dialect of the Coast Salish language Halkomelem), the name Stó:lō means “People of the River” as the Stó:lō primarily rely on the Fraser River and its tributaries for their way of life.

Historically, Stó:lō society was organized in a strict hierarchy; that of Siy:ams (Chiefs or upper class), general populace, and slaves. The Siy:ams, often hunters, held positions of great respect and importance. The slaves were by most accounts treated well, and were given tasks relating to gathering and preparing food or carpentry. The Stó:lō economy was based around a reciprocal exchange program, called the t’leaxet, or potlatch, where villages would gift each other the main delicacies and supplies needed for both survival and pleasure.

Because the river was the main way for transportation, villages were mostly concentrated on the waterway. Longhouses made out of Cedar would house whole families. Depending on the season, families would leave their longhouses and go to different dwellings situated by prime fishing or gathering spots. These dwellings were usually small pit houses made out of timber and built into the ground. Wild berries that grew on the mountains, such as strawberries, thimbleberries, soapberries, and black caps, were a popular food, as well as wild onions, potatoes, and carrots. The Red Cedar tree was a useful resource, and was used as bark, timber, rope, canoes, woven baskets, and art. The most important food source, however, was salmon. A staple food in the diet year round, salmon were considered to be the descendants of a Stó:lō ancestor who had been transformed into the fish by the Great Creator so that the people would never go hungry. As such, the salmon is respected and placed in high respect during ceremonies and spiritual gatherings. This interconnectedness between people and the natural world is still a major part of Stó:lō spirituality. Shxwelí, or life force, connects all living things with the earth, as well as connecting the present with the generations past and future.

Archaeologists place the arrival of the Stó:lō circa 4-10,000 years ago, and Stó:lō oral history claims the region has been inhabited by their people “for time immemorial.” According to Creation Stories, the Stó:lō are descended from the Sky people and the Earth people, and were given their territory, or “Solh Temexw”, by the Great Creator. Oral histories surrounding the Great Creator and the beginning of the world have been passed down through centuries of generations until the present day.

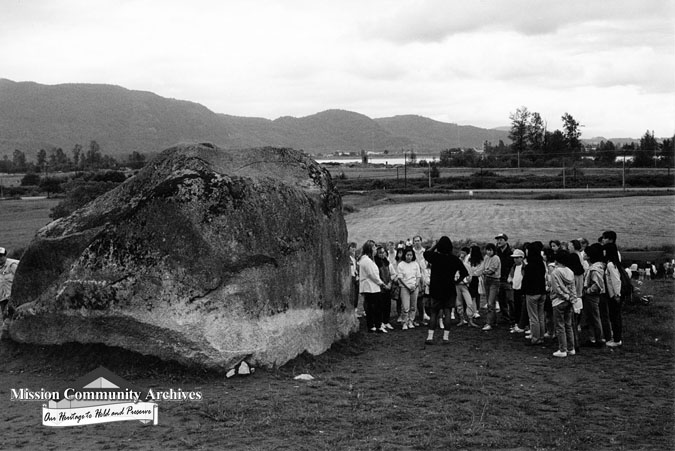

Xay:tem

One such important oral history is that of the Xe:xals, or Transformers, which has a few variations. When the world was very young and the people lived with no guidance, the Great Creator either became the Xe:xals, or appointed the Xe:xals as guardians of the Stó:lō and to show the people how to live. The Xe:xals, three male bears and one female bear, travelled the earth to “make things right” again. People who were productive and good to their communities were transformed into useful commodities, such as salmon, beaver, or cedar, so that the people would never be without. Those who were selfish, and did not preserve their culture or contribute to the community were turned into stone. When the Xe:xals arrived at Hatzic, they found three good chiefs and gave them the gift of written language. The chiefs promised to teach the people the language and to share the gift. However, when the Great Creator returned in the guise of a man, Xa:als, the chiefs had kept the language to themselves. When Xa:als began to turn the chiefs into a stone, the men panicked. One chief began to teach the people as fast as he could, another began to cry, and the last began to sing. The Xay:tem rock still stands, and is said to hold the chief’s song for eternity.

Today, Xay:tem is a National Historic Site. Carbon dating has placed the site as being at least 9,000 years old. Recent archaeological digs have unearthed a longhouse that is believed to be around 6,000 years old, making it the oldest found dwelling in B.C., and one of the oldest in Canada. The importance of such a find has placed Mission as an integral place for not only the Stó:lō, but also in Canadian history.