The Arrival of the Oblates

The Arrival of the Oblates

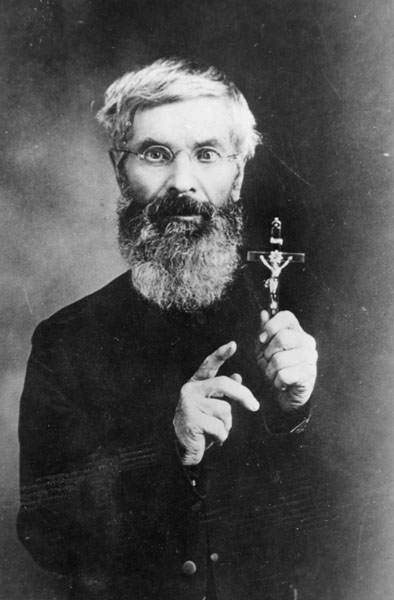

One February day in 1861, an iron war canoe travelling upstream on the Fraser River changed the course of history in the Fraser Valley forever. The canoe carried twelve Stó:lō men and one Father Leon Fouquet, the latter of whom had recently arrived from France on a mission for the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. The Oblates were a new Catholic order, originally established to evangelize and educate the poor, who believed that Satan was at work both in the lives of non-Christians, but also in the corrupt civilization of Christian secular society. Father Fouquet’s intent was to save the Indigenous populations from not only Satan, but from the violent and alcoholic excesses of the prospectors looking for gold in the nearby Caribou Gold Rush.

Looking to find a place in the middle of Stó:lō territory where he could establish a Mission School and Church, he found the perfect spot by a creek overlooking the Fraser River and the mountains, approximately at the bottom of modern day Grand Street where the train tracks are situated. Fouquet set to work, building the grounds which he hoped would soon be used to educate local Indigenous boys.

Many of the Stó:lō were initially happy that Father Fouquet had arrived. Full of the best intentions, the Oblate priest genuinely wished to help the Stó:lō Peoples, who were often badly mistreated by the white settlers and gold prospectors. The Oblate settlement was constructed quickly, with the Oblates and the Stó:lō working alongside each other. It included farmland, orchards, a church, several residences, and a grist mill and sawmill. It even included a post office, where mail would be addressed to St. Mary’s Mission. Because there was a similarly named religious settlement in the Okanagan, the post would be addressed to Mission City. By 1863, the boys’ school was running. In 1868, the Sisters of Saint Ann joined the Oblates to establish a nearby sister school for girls.

Some of the Stó:lō became enthusiastic Catholics, finding the rituals of the Church in many ways similar to their own highly ceremonial spiritual gatherings. Enthusiastic re-enactments of Passion Plays depicting the Crucifixion of Christ drew crowds of thousands of First Nations people. At this time, residential schools had not yet been made mandatory nor earned their infamous reputation, and many families wished for their children to be educated by the Oblate Fathers, willingly sending their children to the school. Father Fouquet and at least one of his contemporaries were staunch advocates for respecting Stó:lō land rights.

The Residential School System

In 1883, the Canadian Pacific Railway requisitioned the land on which Father Fouquet built the Mission, and St. Mary’s Mission moved (with reluctance) uphill to their second location in what is now Fraser River Heritage Park. But by the 20th century, many of the school’s methods for governing the Mission were dictated by the Federal government’s policies, which were intended to suppress all First Nations culture with the goal of assimilation via the destruction of their cultures, communities and heritage. Following the establishment of these laws, indigenous children were required to attend residential schools, and were not allowed to see their families for a minimum of six years in the hopes that the absence would break cultural and family ties. They were forbidden from speaking their mother languages, and children were faced with harsh punishment as a consequence if this rule or any other rules were broken.

In 1961, the Oblate school was closed down, and a government-run school was erected east of the second site. By the 1970s, the school buildings were used as a residence for Indigenous students who lived too far away to attend the Mission Public Schools. The residence was closed in 1985, making it one of the last residential schools to close in Canada.