Shaping our Community:

Prominent Indo-Canadian Pioneers

Indo-Canadian Pioneers

Throughout its history, Mission has been home to many Indo-Canadian pioneers who have shaped the town. First arriving in B.C. in 1903, thousands of Indian men worked on the railways or in the sawmill industry, looking for better economic conditions than their home country. Disliked by a racist government at the time, it was a terribly difficult existence. Government policies designed to keep Indians out of the country were mostly effective, and only a small number were able to live in the province. As a result, Mission did not have a large Indo-Canadian population until the 1940s.

Slowly, the town began to attract the first Indo-Canadian pioneers, looking for work in the sawmill industries. Mostly hailing from the Punjab state in India, and belonging to the Sikh religion, they were known to be extremely hard-working. Young men, little older than boys, would leave their families and travel to Canada looking for new opportunities. By the 1930s, four Indo-Canadian men built a small steam mill powered by horses on the Hatzic Prairie. At that time, only a handful of Indo-Canadian families lived in Mission.

Mission’s role as a major berry producer diminished after the Japanese-Canadian internment, and the town was forced to rely on other industries. The lumber and sawmill industry soon became prevalent, and Indo-Canadian entrepreneurs were able to take advantage of these opportunities. Soon, Mission was home to a number of men who were both important benefactors for the Indo-Canadian community and Mission itself.

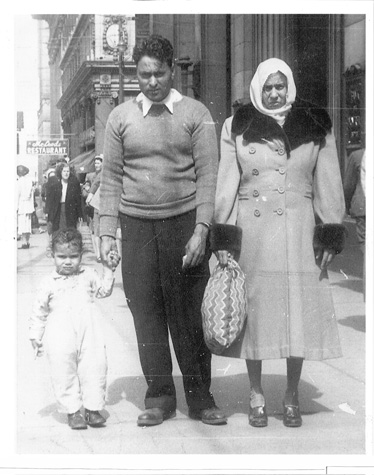

In 1947, Indo-Canadians were finally given the right to vote, and the quota policies were expanded as well, allowing men to return to India to marry or bring their families over. Businessman Indar Singh Gill, owner of Indar Fuels, had not seen his wife and son since he had left his village via camel in 1930 when he was seventeen. He returned with his family by ship, docking in Hawaii where he bought his wife her first set of Western clothes. At that time, turbans and traditional Indian clothes were banned in some businesses, and the Indo-Canadian community felt the pressure to fit in.

During the 1940s, many Indo-Canadian men established businesses in the Mission area. After WWII, approximately 15-20 sawmills were owned by Indo-Canadians. In the 1950s, Indar Singh Gill expanded his fuel company, Indar Fuels, and bought Fraser Valley Sawmills, where he employed 30-40 men. In 1964, a fire broke out and unfortunately the mill was lost but by this time many other Indo-Canadian entrepreneurs had been established.

Mission was mostly welcoming to the new residents. Mr. Tok Herar remembers the citizens being hospitable, quickly befriending other young men from different backgrounds. Joining sports teams gave everyone a common passion, and camaraderie was high. When his wife, Kuldip, arrived from India in the 1960s, the ladies belonging to the local Rotary Club ensured her every need was met while she adjusted to the new culture.

The Braich Empire

Herman Singh Braich was a boy living in the little village of Braich, Punjab, when he spotted two cobras fighting in the brush. Having heard the legend that killing a cobra would bestow great courage, he killed both snakes with his bare hands. Whether or not that action forged what was to come, two years later he bravely left his village, family, and everything he knew, lying to the authorities by claiming he was sixteen (two years older than he was) so that he could bypass the age limit and board a ship bound for Canada.

When he landed in Victoria, he quickly found work in forestry and studiously learned every trade within the sawmill industry, swiftly moving up the ranks. A shrewd young man, he worked hard and saved all his money so that he could take advantage of new opportunities as they arose.

In the late 1940s, he discovered Mission and felt it was the perfect place to start his own venture. In the wake of the 1948 flood, land on the flats was inexpensive. Building Herman Mills in 1950 in the flood zone was a risk, but again his courage paid off. He realized his prime location on the river could be utilized, and turned the flood risk to his advantage by building a lumber barge and loading facility.

In this fashion, Mr. Braich quickly gained success and the respect of the Mission community.

Little India

At that time, the only way to immigrate from India was to find a sponsor from Canada, and Herman Singh Braigh became a patron of many such men, believing that he could provide the opportunity for his countrymen that he had enjoyed. Vouching for their character, he employed the newcomers at his industries. It is estimated that hundreds of men came to the area through the opportunities offered by Braich. In 1959, he built a bunkhouse on the mill grounds that could house his labourers. Guaranteeing free accommodation, the recent immigrants could save money and become established enough in Canada to bring their families over from India, or to buy land and start businesses themselves. Many settled on vacant land in the Mission flats which soon became known as “Little India.”

In 1968 Herman Mills burnt down, which was a catastrophic loss for the Indo-Canadian community. An estimated 128 families moved away (over 1,000 people); many had lost their jobs. A new mill was built later in 1974 on the exact same site, but Abbotsford had by this time overtaken Mission in size and economic importance, and many chose to move there where there was also a growing Indo-Canadian community.

Mr. Braich continued to be an important character in Mission. A generous man who believed in giving back, he donated to a number of charitable causes and organizations, including the Mission Hospital. When he died in 1976, his loss was felt not only by his large family, but also the town where he had invested so much. The Braich family still continues to call Mission their home; as his son stated, “Mission’s soil is in our blood.”

Naranjan Singh Grewall

Possibly Mission’s most legendary character, Naranjan Singh Grewall was a trailblazer in more ways than one. Passionate and visionary, his life story reads like a movie script. British Columbia’s first Indo-Canadian to be elected to public office, he was also a pioneer in the logging industry. Hailed by the Fraser Valley Record as a “public-spirited citizen” and well-liked for “his fighting spirit and general love of life,” his unfortunate and untimely death cut short his extraordinary presence.

In 1925, he arrived in Canada at the age of seventeen from the small village of Dhudike, Punjab, finding work in the sawmill industry. By 1941 he had moved to Mission and was employed as a millwright at Fraser Mills. A hard worker and sharply intelligent, he rose quickly through the ranks and soon became a foreman in the company. Deeply passionate about workers’ rights, he was elected as the union representative. He beat out several prominent mill-owners at the land auction after the Japanese evacuation of 1942 to buy both the Kamamura Mill (Riverside Sawmills), and Mission Sawmills. At the same time, he bought Prairie Lumber Company, previously owned by Indo-Canadians.

He consolidated these businesses into Mission Sawmills Ltd, and also branched out into other economies in the logging industry. He soon was the owner of six companies: Mission Sawmills Ltd, Mission Forest Products Ltd, Slesse Creek Logging Co Ltd, Firbank Logging Co Ltd, and Sujan Investments Ltd. These companies were a major source of jobs for Indo-Canadians in the area, as well as the rest of Mission.

Trailblazer

Married to Helen Barrie, a Canadian-born Caucasian woman, the Grewalls, along with their three small children, were involved in many community and political matters and were regulars in Mission’s social scene.

As a community-minded man, Mr. Grewall sat on the directory of a number of charitable boards. This experience encouraged him to become involved in municipal politics, namely with the CCF political party (now the NDP). Believing that “democratic privileges also carry obligations and duties,” he also ran for a position on the Board of Commissioners of the Corporation of the Village of Mission in 1950.

Already a popular and well-respected man, he topped the polls, beating out seven candidates in a historic victory, especially given that Indo-Canadians had only been given the right to vote three years before. While Indo-Canadians had gained respect in business, racism still existed, especially regarding elite positions in society. The Vancouver Daily Province newspaper ran an article with the headline, “First in BC and believed first East Indian in Canada to hold public office.” He was re-elected in 1952, and again in 1954. The same year the Board unanimously voted to name him Chairman of the Board, which gave him similar duties and influence to that of a Mayor. During his years in public office, he continued his community involvement and large-scale business ventures. He also fought for the building of a new Mission bridge as well as against prohibitive diking taxes.

Fighting Corruption

Naranjan Singh Grewall was even more passionate about the Forestry industry. At that time, the SoCred government in provincial power was embroiled in a corruption scandal. The Minister of Forestry was suspected of giving away significant amounts of timber rights to previously declined lumber corporations, often his personal friends. Worse, the premier W.A.C. Bennet seemed to be purposefully looking the other way. This infuriated Mr. Grewall, who termed the present holders of forest management licenses “timber maharajas”, believing that the current system could revert to a form of feudalism he had left behind in India.

Forestry was B.C.’s largest economic driver at the time, and the scandal affected many. Chief Justice Sloan held a commission on the forestry issue in 1955. Mr. Grewall wrote a brief to the commission arguing for the rights of small municipalities to own forests within their boundaries, instead of the provincial government leasing the land to large logging companies. Soon after, the Minister, Robert Sommers, was charged with bribery and served time in jail.

Given his passion for the issue, Mr. Grewall was given the responsibility by the CCF to oversee much of the timber file of BC. Following the socialist party line, he was an outspoken and passionate defender of the right of small companies to be given equal opportunities to that of the large corporations, and for that right to be protected by the government. He even got into a public argument with the Premier at a town hall meeting. Because of his integral role in these affairs, Mr. Grewall ran as the CCF candidate for MLA in the 1956 provincial election however his campaign was not successful.