The Lost Pioneers:

Mission’s Japanese Canadians

The Issei Arrive

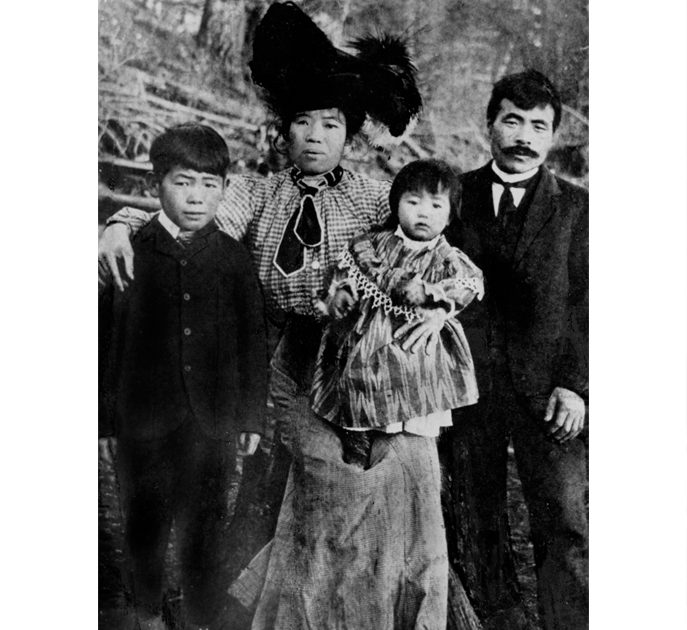

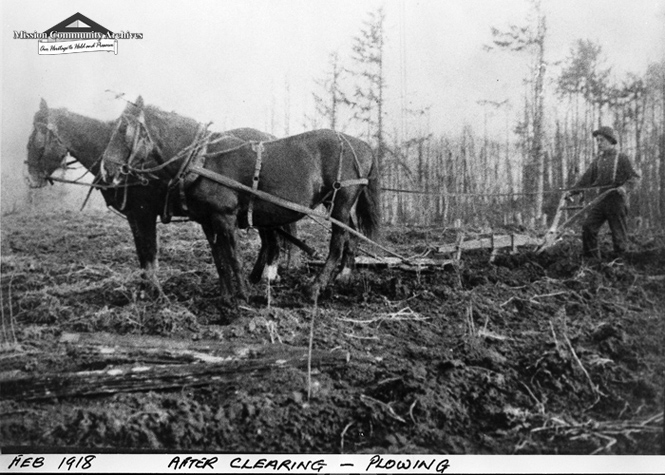

In 1904, the first Issei (Japanese word for a first generation immigrant) arrived, Mr. Kumekichi Fujino. After raising money working in the saw-mills of Vancouver, he bought 30 acres of forested, hilly land in Mission, then sent for his wife, Sueno, and their son, Eljiro, from Japan. He then set to clearing the land with only hand tools, dynamite, and a horse and plough. The work was back-breaking and exhausting, but even in this foreign and sometimes inhospitable land, small luxuries and comforts from the home land were treasured, like the bathhouse he built as an addition to the family home.

Soon after, many other Japanese pioneers arrived, attracted by the opportunities afforded by cheap farmland. Kaich Senda arrived and established a berry farm. In 1910, Tashiro Hashizume purchased a 10 acre farm at the foot of Mt. Mary Ann. He had already tried his hand farming on unsuitable land in Alberta, so he was no stranger to hard work. Luckily, his perseverance was rewarded in Mission. Though his plot of land was entirely covered by forest, he succeeded and planted strawberries, rhubarb, fruit trees, and potatoes. When he died in 1938, he had 32 employees. Today, many enjoy the fruits of his labour when walking around the beautiful grounds of his former home, now Westminster Abbey!

The Nokkai

Over the next forty years, roughly 111 Japanese families settled in the Mission area. Unlike Chinese immigrants, who were largely unable to bring their families to Canada due to the punitive head tax, Japanese men were able to establish their families in the region and integrate more fully into the community.

In 1916, the Japanese farmers established the Nokkai, a collaborative farming co-op that worked to launch their produce into the Canadian market, which could often be alienating to non-White immigrants. A hall was built to house the co-op and provide a space for meetings and social gatherings. More than just an agricultural business, the Nokkai represented the entire Issei community, providing a link to the rest of Mission. Entering into community events like the May Day parade and providing volunteering services at the hospital, the Nokkai worked in a similar way to that of an embassy, paving the way for the Issei to become fully integrated in the community.

Community Life

Japanese children were sent to a kindergarten, established in 1918 at the Nokkai hall, where they learned to speak English. Mrs. Emma Barnett was a beloved teacher, a life-long friend to the Japanese-Canadian community, and kept detailed records on each of her pupils. The kindergarten provided easy access into the Mission public school system, and the Japanese-Canadian children excelled at academics.

Although cultural and language differences still separated the Issei from the community, the Nissei children (descendants from Japanese forefathers) integrated more easily. They joined Mission sports teams and clubs, which helped ensure a generation of Mission’s children grew up without much noticing the ethnic differences amongst them. By the 1940s, the Nissei made up approximately 30% of the population at the Mission schools. Issei parents recognized the importance of a Canadian education, but also desired their children to grow up with an understanding of their cultural heritage and identity. A Japanese Language school was created for Saturday study, and was run by Mr. and Mrs. Kudo, two prominent members of the Issei community. As a result, Nissei children worked very hard, both on the farm and at school, and grew up with a transnational identity, Japanese and Canadian.

In 1928, a Buddhist Church was built on the corner of farmer Mr. Miyagawa’s property, and was an important cornerstone of the Japanese community, providing another space to practice Japanese culture and tradition. Mr. Kudo, also a devout Buddhist, acted as a lay minister during the times when no ordained priests were available. The Fujinko, or women’s club, would provide training for girls to become a house-wife and run a farm and the Judo club was a popular activity with the boys.

Achievements in Agriculture

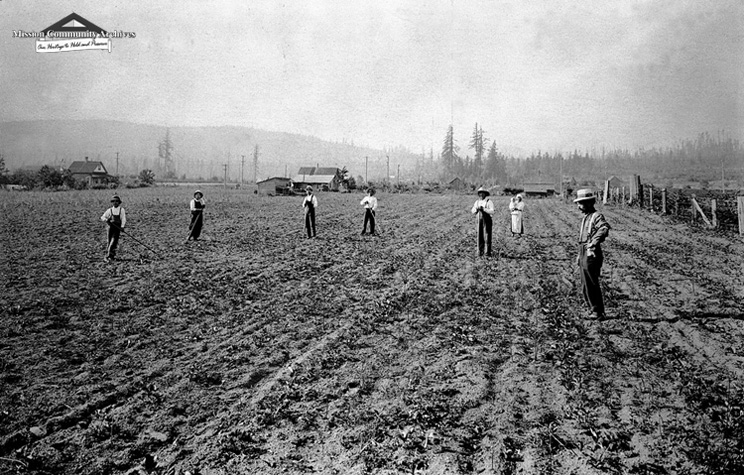

The Issei soon established themselves as very hard working citizens of Mission, recognized for their admirable feats of transforming the thick brush on the hills into fertile farmland, and helping to build a thriving farming community. The Issei farmers grew mostly berries, and shipped their crops internationally via rail and ship. Bunjiro Sakon, a brilliant agriculturalist, bred two popular and useful crops: a hothouse rhubarb, designed to thrive inside a greenhouse, and an Autumn Strawberry, which could fruit in colder weather. These crops significantly extended the growing season, allowing farmers to profit from the produce much longer.

Working within a quota system, the farmers of the Nokkai would take turns growing certain crops so that the market wouldn’t become saturated, ensuring everyone would make a decent living. The Nokkai soon became such an important local force that non-Japanese farmers wanted to join. As a result, the Pacific Cooperative Union (or PCU) was formed in 1932 with 120 produce farmers. Approximately 75% of the members were Issei farmers, but as a testament to their hard work, grew 90% of the produce. By this time, partially because of the business ties that connected them, the relationship between the Japanese-Canadians and the rest of Mission was strong.

Pearl Harbour

On December 7, 1941, everything changed. Japan entered WWII, attacking the US Military base on Pearl Harbour, which lead to both Canada and the US declaring war on Japan. Overnight, Japanese-Canadians were added to the list of potential enemy aliens. Suddenly regarded as spies, calls began from various groups seeking mass deportation of the Japanese, regardless of citizenship. Although Mission’s Japanese-Canadian residents had supported the war effort by buying the most war bonds prior to Japan’s attack, they were still viewed by some as potential enemies.

Under the War Measures Act, Japanese nationals were arrested, subjected to mandatory registration and fingerprinting, their schools and newspapers closed, curfew imposed, and a telephone ban enforced.

Many of Mission’s residents stood by their Japanese-Canadians friends. Letters of support were published in the Fraser Valley Record but at least one Anti-Japanese meeting was held in Mission in 1942.

Mission’s Japanese-Canadian residents were given an extension to allow time to plant their crops, but in April 1942 residents were given their orders to go and relinquish all financial assets to a “Custodian for Enemy Alien Property” for “safekeeping.” Without knowing the full extent of what was ahead, many of Mission’s Japanese-Canadian residents took few precautions, believing that the war would soon be over and they would be allowed to return home. Some residents transferred property to the kindergarten teacher Mrs. Emma Barnett and PCU manager Mr. Shimek, but these transfers were later discovered and reversed by the Custodian for Enemy Alien Property.

Mr. Kudo and his family were one of the last to leave. Because of his leadership role in the community, he worked with the authorities to ensure the evacuation was as peaceful and respectful as possible.

Aftermath

Less than a year after the evacuation, all confiscated possessions were “disposed of” by the Custodian for Enemy Alien Property at auctions, the rightful owners receiving nothing. This included at least 90 farms (totaling over 1,400 acres of land), and at least 100 vehicles. A ban was put in place denying any Japanese-Canadians the right to return to B.C.

Many of Mission’s Nissei ended up in Picture Butte and Raymonde, Alberta working on the sugar beet farms. The living standard was very poor. Chieko Nishiyama, (nee Amemori), remembers arriving at her placement at a farm in Raymonde, Alberta and “crying her heart out” after finding her living conditions to be a granary with no roof. Other families, often with over ten members, were housed in tiny remodeled chicken coops or sheds. Many remember their residences as cold and miserable. Mrs. Sueno Ikeda (nee Fujino), pregnant with two small children, couldn’t handle the hard physical labour of the sugar beet farms, and struggled to find other work.

Back in Mission, the loss was felt economically as well. Prior to the evacuation, the berry yield in 1941 had been 190 freight trains, and the year after the evacuation dropped disastrously to only 30 trains. The non-Japanese farmers that took over the farms had neither the knowledge nor the work ethic of the previous inhabitants. Mission’s status as a reigning berry capital was over.

Homecoming

Fujikawa Family

Only a few of the Nissei chose to return to Mission. The Fujikawa family was an anomaly; they had managed to retain their land by intermarrying into the Caucasian population. As such, the property laws surrounding the internment had not affected them, and interned family members returned to the family farm in Silverdale.

Gilbert & Emiko Shikaze

Siblings Gilbert and Emiko Shikaze returned to Mission with their families after the ban was lifted, buying farms in Dewdney and Hatzic. Later, both of them relocated to nearby Aldergrove.

Fred & Tomiko Imakire

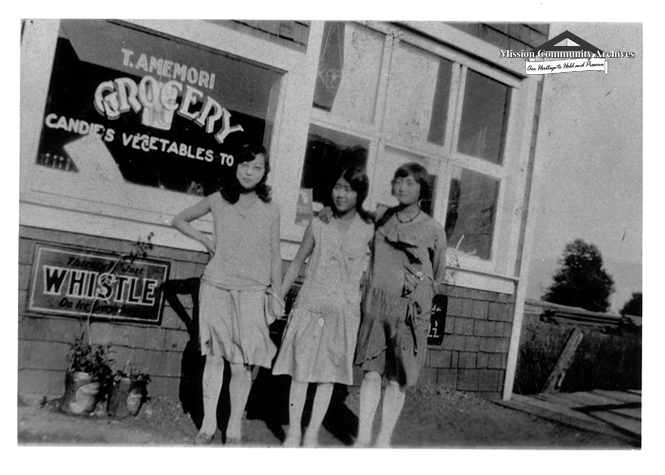

One other Nissei family returned to Mission; Fred and Tomiko Imakire. Tomiko was the daughter of Tarou and Asa Amemori, the owners of the Japanese grocery store who had settled in Mission in 1920. Tomiko and Fred were evacuated to Raymonde, Alberta with Tomiko’s sister and their small children, but were later relocated to another internment camp in Tashme, BC. After returning to the Mission flats in 1949, the Imakires quickly regained the respect that the Nissei had previously established. A talented seamstress, Mrs. Imakire was known both for her fashionable and generous presence. When she died in 2004 at the age of 89, her years of dedication to volunteering in the community was greatly missed.